More than a century after the Tulsa Race Massacre, we’re still getting the story wrong.

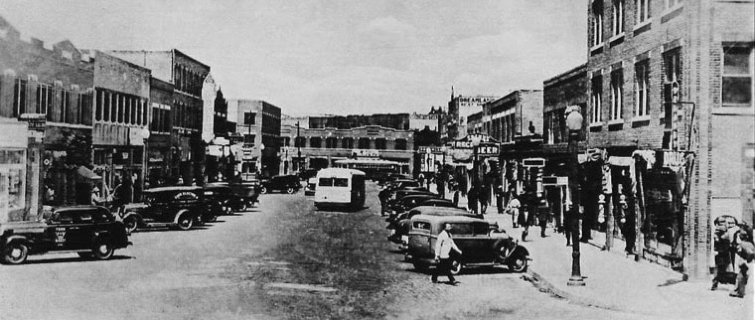

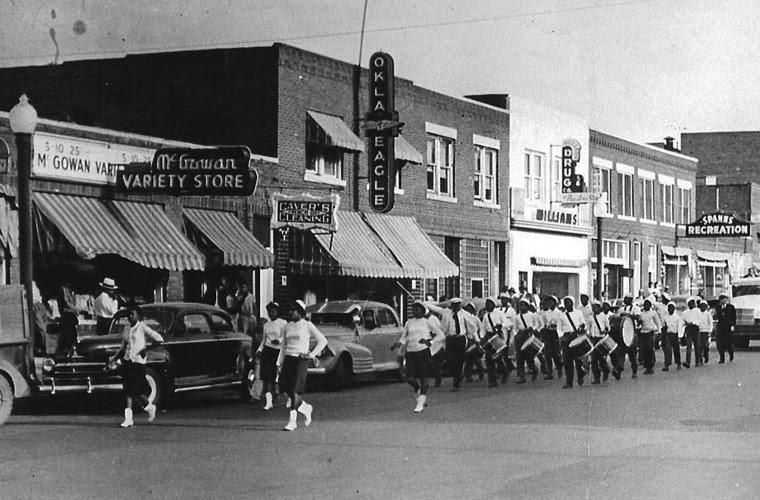

At least there is a story. For decades after a white mob destroyed the prosperous Black district of Greenwood in 1921—killing hundreds of residents, burning and bombing 35 city blocks, and displacing thousands—the violence went mostly unacknowledged in history texts. That changed with the appointment of the Tulsa Race Massacre Commission, which issued a report in 2001 confirming those facts and calling for, among other things, direct payments to the few elderly survivors who were still alive.

Today, we know much more about the massacre—one of the worst cases of domestic terrorism in U.S. history—and how it decimated a neighborhood commonly known as “Black Wall Street,” leaving the community the shell of itself that it is today.

But that account isn’t quite right, either.

“The name ‘Black Wall Street’ wasn’t used until after the massacre,” says Cody Brandt, a Tulsa native and graduate of the Master’s in Real Estate program at Georgetown University who works as an appraiser for JLL, a global real estate investment company. In fact, almost immediately after the attack, residents and businesses launched a furious effort to bring the community back—and largely succeeded.

“Tulsa’s Black residents rebuilt the neighborhood bigger and stronger than it was before,” Brandt says, despite attempts by white residents to stop those efforts through rezoning and the adoption of highly burdensome building codes. “It wasn’t until the highways were proposed [in the 1960s] and urban renewal came that the entire neighborhood was completely wiped out for a second time.”

Divided and Dispersed

For his final project at Georgetown, Brandt wrote a Capstone paper, “Promoting Economic Development Through Removing Freeways,” that called for dismantling sections of Tulsa’s Inner Dispersal Loop (IDL), which all but destroyed Greenwood and other downtown neighborhoods in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s.

This highway and others like it around the country were built to provide quick access to the fast-growing (and overwhelmingly white) suburbs—and in this effort they were wildly successful. While never the intent of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1956, the interstates carved up urban centers and low-income and minority neighborhoods. Homes and businesses were lost to the government’s power of eminent domain, which led to more depopulation, falling property values, and neighborhood decline.

These “urban renewal” projects did not hurt only minority and low-income communities. Tulsa, like other U.S. cities that essentially hollowed out much of their downtowns, lost revenue as once-vibrant commercial and residential areas gave way to hundreds of acres of underused property.

“Today, downtown Tulsa has demolished large portions of its urban fabric surrounding the high-rise office district in exchange for surface commuter parking that sits largely vacant during weekday evenings and weekends,” Brandt says. “The loss of density and population has made funding city operations more difficult as the tax money collected has become more diluted as density declines.”

Brandt has discussed the financial repercussions of these policies with the Tulsa City Council and various political and community leaders. He has also spoken at conferences of the Urban Land Institute and the Congress for the New Urbanism.

Other cities—among them Portland, San Francisco, Milwaukee, and Chattanooga—have removed inner city highways to preserve historic neighborhoods and stabilize their populations, while others have opted for partial removal, Brandt writes. He makes the case that Tulsa could benefit financially and improve its residents’ quality of life by using federal highway funds to remove parts of Tulsa’s IDL that have had a significant impact on Greenwood.

‘Nothing Sacred About the Status Quo’

Brandt is part of a coalition that has applied for a planning grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program (RCP), which the department calls “the first-ever Federal Program dedicated to reconnecting communities that were previously cut off from economic opportunities by transportation infrastructure.”

“There’s nothing sacred about the status quo,” U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg said when announcing the program in 2022. “These highways, roads, and railways aren’t rivers, lakes, or mountains, they’re not divinely ordained. They’re decisions. And we can make better decisions than what came before.”

The coalition wants to redirect traffic now using the Inner Dispersal Loop to other regional highways. This would allow the city to rebuild boulevards that made up the historic street grid prior to the construction of the IDL. The intent is to facilitate local traffic flow within the rebuilt street grid and add vibrancy to the neighborhood while discouraging regional traffic through the urban core. A competing application for RCP planning grants, submitted by the Oklahoma Department of Transportation, would not remove the highway anytime soon, but would use the funds to study ways to “mitigate” the IDL’s impact on Greenwood with improved lighting, landscaping, and other amenities. The agency said that any project to dismantle the highway could not start for 30 or more years.

Brandt and other community advocates strongly disagree with that notion and are advocating for more immediate action.

“These are two very different visions,” Oklahoma State Representative Regina Goodwin, a descendant of a survivor of the 1921 massacre, told the online publication “Route Fifty,” which covers issues involving state, county, and municipal governments.

“It’s very difficult to collaborate with the department of transportation when they want to expand and when we want removal,” added Goodwin, a Democrat who was recently named her delegation’s Assistant Minority Floor Leader. “They don’t want to look at removal for 30 years. I might not be alive in 30 years, but I guarantee you an interstate could be built in 30 years. They have no intention of removing that segment.”

The U.S. Department of Transportation is expected to make a decision on the grant requests as early as February.

In the meantime, Brandt remains committed to a vision that many in Tulsa have nurtured for years and that he has worked on since he was a student at Georgetown eight years ago.

“I think it’s terrific that one of our students is doing something which we encourage all of our students to do with Capstones, which is to pick a project where you might actually do the project,” says Glenn Williamson, faculty director of Georgetown’s Real Estate program. “He’s someone who took an academic exercise from eight years ago, and he’s continuing to pursue it.”

Jamie Pierson, an urban planner and designer of public art in Tulsa, says Brandt was one of many from the city who have made a personal commitment to the project.

“It’s been taken as sort of a given by most people in the know and involved in these issues that the highway has needed to be removed for a long time,” Pierson says. “But Cody was one of the first people who said, ‘OK, well, let’s do it. Let’s figure out the steps to do it.’”

Update

On Feb. 28, 2023, the U.S. Department of Transportation announced that it had chosen the citizen group’s grant proposal, which prevailed over a competing plan submitted by the City and the Oklahoma Department of Transportation. The grassroots group, represented by the North Peoria Church of Christ in Tulsa, will receive $1.6 million to study the removal of the part of the Inner Dispersal Loop that cuts through Greenwood.

The grant is among 45 proposals awarded nationwide, totaling $185 million, through the federal Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program.

“Transportation should connect, not divide, people and communities,” Buttigieg said in a prepared statement. “We are proud to announce the first grantees of our Reconnecting Communities Program, which will unite neighborhoods, ensure the future is better than the past, and provide Americans with better access to jobs, health care, groceries and other essentials.”

Warren Blakney, the church’s senior pastor, told television station KTUL that winning the grant would not have been possible without the hard work of community members.

“I’m simply amazed,” he said. “I’m pleased. I’m marveled.”